“Mindfulness hype” challenged by integrative health researchers

October 19, 2017

by John Weeks, Publisher/Editor of The Integrator Blog News and Reports While enjoying some positive feedback on an editorial I recently wrote based on research that supported expansion of mindfulness practices, a paper arrived electronically from a colleague who is a neuroscientist and yoga therapist. While my editorial was, effectively, a promotion of more rapid uptake of mindfulness practices, the consensus document sent by my colleague – who had not yet seen my editorial – at first blush slapped down my perspective as “mindfulness hype.” The column I wrote for the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (JACM) had a hype-ish title: “’Mind Matters, Money Matters’ Revisited: Anticipated and Unanticipated Economic Benefits of Mind–Body Care.” (Available here on open access here until October 31, 2017). Recent papers from researchers at the Rand Corporation and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute covered here in Integrative Practitioner stimulated the column. I’d linked their studies, that showed effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness to a positive JAMA commentary in response – in its own way “hype-ish” – to one of them. Then I linked to a 2016 study from the pioneering Benson-Henry Institute on mindfulness research that concluded with a strong charge that “the beliefs and biases that delay the use of psychosocial interventions need to be challenged.” They took a further step into a very hype-ish advocacy with a policy recommendation suggesting that “the data suggests that mind body interventions should perhaps be instituted as a form of preventative care similar to vaccinations or driver education.”

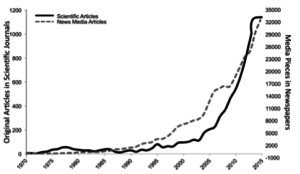

by John Weeks, Publisher/Editor of The Integrator Blog News and Reports While enjoying some positive feedback on an editorial I recently wrote based on research that supported expansion of mindfulness practices, a paper arrived electronically from a colleague who is a neuroscientist and yoga therapist. While my editorial was, effectively, a promotion of more rapid uptake of mindfulness practices, the consensus document sent by my colleague – who had not yet seen my editorial – at first blush slapped down my perspective as “mindfulness hype.” The column I wrote for the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (JACM) had a hype-ish title: “’Mind Matters, Money Matters’ Revisited: Anticipated and Unanticipated Economic Benefits of Mind–Body Care.” (Available here on open access here until October 31, 2017). Recent papers from researchers at the Rand Corporation and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute covered here in Integrative Practitioner stimulated the column. I’d linked their studies, that showed effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness to a positive JAMA commentary in response – in its own way “hype-ish” – to one of them. Then I linked to a 2016 study from the pioneering Benson-Henry Institute on mindfulness research that concluded with a strong charge that “the beliefs and biases that delay the use of psychosocial interventions need to be challenged.” They took a further step into a very hype-ish advocacy with a policy recommendation suggesting that “the data suggests that mind body interventions should perhaps be instituted as a form of preventative care similar to vaccinations or driver education.”  In short, an apparent bullseye for the critical paper: “Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation.” The 15 authors behind this “majority consensus” document shared analysis and recommendations that began in a 2014 invitational meeting funded by the Mind and Life Institute. That institute was founded by mindfulness pioneer Richie Davidson, PhD, and is chaired by his partner of 25 years, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. The sterling team includes, for instance (L-R in the photos): David Vago, PhD, from the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Vanderbilt; Clifford Saron, PhD, from the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain; Sara Lazar, PhD from the Center for Mindfulness at U Massachusetts Medical School; and the collaborator who sent me the paper, Laura Schmalzl, PhD, the editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy and professor at Southern California University of Health Sciences. The lead author is Nicholas Van Dam, PhD, at the Ican School of Medicine. The context for the paper is the rapid spread of mindfulness “from being a fringe topic of scientific investigation to being an occasional replacement for psychotherapy, tool of corporate well-being, widely implemented educational practice, and ‘key to building more resilient soldiers.’” They might also have mentioned an article that recommended that everyone be delivered the program like a vaccine.

In short, an apparent bullseye for the critical paper: “Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation.” The 15 authors behind this “majority consensus” document shared analysis and recommendations that began in a 2014 invitational meeting funded by the Mind and Life Institute. That institute was founded by mindfulness pioneer Richie Davidson, PhD, and is chaired by his partner of 25 years, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. The sterling team includes, for instance (L-R in the photos): David Vago, PhD, from the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Vanderbilt; Clifford Saron, PhD, from the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain; Sara Lazar, PhD from the Center for Mindfulness at U Massachusetts Medical School; and the collaborator who sent me the paper, Laura Schmalzl, PhD, the editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy and professor at Southern California University of Health Sciences. The lead author is Nicholas Van Dam, PhD, at the Ican School of Medicine. The context for the paper is the rapid spread of mindfulness “from being a fringe topic of scientific investigation to being an occasional replacement for psychotherapy, tool of corporate well-being, widely implemented educational practice, and ‘key to building more resilient soldiers.’” They might also have mentioned an article that recommended that everyone be delivered the program like a vaccine.  The paper targets the confounding diversity in mindfulness and meditation practices, and not-surprisingly then, in the published scientific literature. On the one hand, elaborate, multi-week, well-researched programs such as the cornerstone Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs founded by Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD. The programs featured at the Benson Henry Institute are another at this end of the spectrum. On the other, internet or App-based programs, or maybe a series of three or four 20-minute sessions. Outcomes, similarly, may be based on neuroscientific exploration of the practices of Buddhist monks or self-reports of students recently exposed to the practice. Not only different animals, but different farms altogether. Yet someone affiliated with the limited training may well pitch the outcomes from the former.

The paper targets the confounding diversity in mindfulness and meditation practices, and not-surprisingly then, in the published scientific literature. On the one hand, elaborate, multi-week, well-researched programs such as the cornerstone Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs founded by Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD. The programs featured at the Benson Henry Institute are another at this end of the spectrum. On the other, internet or App-based programs, or maybe a series of three or four 20-minute sessions. Outcomes, similarly, may be based on neuroscientific exploration of the practices of Buddhist monks or self-reports of students recently exposed to the practice. Not only different animals, but different farms altogether. Yet someone affiliated with the limited training may well pitch the outcomes from the former.  The consensus team offers three tables meant to provide clarity in future research. These are yet intriguing for non-researcher clinicians or mindfulness-interested humans. Eight varying self-report questionnaires are presented that guarantee – to move to a different part of the farm -- that apples will be compared to peaches and lemons. The focus of some is “awareness.” In others it is “acceptance” or “attention” or “non-reactivity” or “body mindfulness.” The consensus team recommends that in future studies researchers be specific about which of the defining features they are using to characterize meditation practice. A lengthy list of “design features” are provided co further clarify distinctions among different studies. One area of potential surprise, explored at length by the authors, is poorly documented harmful or adverse effects. “Much of the public news media has touted mindfulness as a panacea for what ails human kind, overlooking the very real potential for several different types of harm.” These range from “relaxation-induced panic and anxiety” to “depression, negative emotions and anxiety” among individuals with prior trauma to “misleading vulnerable patients.” There are also cases of practitioner-reported “meditation-induced” psychosis, mania, depersonalization, “traumatic memory re-experiencing and other forms of clinical deterioration.” In addition, people using potentially ineffective mindfulness practices over a “well-established therapy” was suggested as a huge “opportunity cost” and “may be a widespread ‘side-effect’ of mindfulness based intervention hype.” The authors conclude with a series of recommendation then add a final touch: “Only with such diligent multipronged future endeavors may we hope to surmount the prior misunderstandings and past harms caused by pervasive mindfulness hype that has accompanied the contemplative sciences.”

The consensus team offers three tables meant to provide clarity in future research. These are yet intriguing for non-researcher clinicians or mindfulness-interested humans. Eight varying self-report questionnaires are presented that guarantee – to move to a different part of the farm -- that apples will be compared to peaches and lemons. The focus of some is “awareness.” In others it is “acceptance” or “attention” or “non-reactivity” or “body mindfulness.” The consensus team recommends that in future studies researchers be specific about which of the defining features they are using to characterize meditation practice. A lengthy list of “design features” are provided co further clarify distinctions among different studies. One area of potential surprise, explored at length by the authors, is poorly documented harmful or adverse effects. “Much of the public news media has touted mindfulness as a panacea for what ails human kind, overlooking the very real potential for several different types of harm.” These range from “relaxation-induced panic and anxiety” to “depression, negative emotions and anxiety” among individuals with prior trauma to “misleading vulnerable patients.” There are also cases of practitioner-reported “meditation-induced” psychosis, mania, depersonalization, “traumatic memory re-experiencing and other forms of clinical deterioration.” In addition, people using potentially ineffective mindfulness practices over a “well-established therapy” was suggested as a huge “opportunity cost” and “may be a widespread ‘side-effect’ of mindfulness based intervention hype.” The authors conclude with a series of recommendation then add a final touch: “Only with such diligent multipronged future endeavors may we hope to surmount the prior misunderstandings and past harms caused by pervasive mindfulness hype that has accompanied the contemplative sciences.”  Comment: On finishing reading the article, I was happy to conclude that my editorial is not exactly in the cross-hairs of the hype criticism. The research I featured in “Mind Matters, Money Matters Revisited” was from the MBSR and Benson-Henry programs. The strong “hype-like” public health suggestions of the Benson-Henry group that mindfulness training should be approached like vaccines or drivers’ education was similarly based on these two well-researched methods. Pleasing to not be on the bad side of the Dalai Lama people. Three additional points. One is the team’s “ironic” suggestion that one form of error in the outcomes may stem from success in a mindfulness program. A person enters with limited sense of self and thus engages poor self-reporting on a “pre” test. Then, “if mindfulness-based enhancements of introspective accuracy are real,” participants may then be self-reporting from a significantly more honest perspective. Gaining insight may make one honestly worse. The data are skewed. Second, the adverse effects are intriguing from the perspective of a “healing crisis” that can happen in whole person care. Peel back a layer and who knows what might emerge. Anxiety may be a good thing. Optimally those offering mindfulness services will have the skills to manage what they awaken. Finally, erring on the side of “hype” will likely be a good thing while this new research agenda is carried out. In our culture, mindfulness may be reasonably viewed as generally wanting. Baby starts, booster shots and transformative practices may all be useful. While we await the new clarity and research precision, I will favor over-medicating with mindfulness and meditation practices, and risking the adverse effects. And I’ll hold to the proposition from the Benson-Henry group that our population health will flourish if everyone, early in life – or later - had a chance to immerse themselves in a multi-week, mindfulness training program. Editor’s note: This analysis article is not edited and the authors are solely responsible for the content. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Integrative Practitioner.

Comment: On finishing reading the article, I was happy to conclude that my editorial is not exactly in the cross-hairs of the hype criticism. The research I featured in “Mind Matters, Money Matters Revisited” was from the MBSR and Benson-Henry programs. The strong “hype-like” public health suggestions of the Benson-Henry group that mindfulness training should be approached like vaccines or drivers’ education was similarly based on these two well-researched methods. Pleasing to not be on the bad side of the Dalai Lama people. Three additional points. One is the team’s “ironic” suggestion that one form of error in the outcomes may stem from success in a mindfulness program. A person enters with limited sense of self and thus engages poor self-reporting on a “pre” test. Then, “if mindfulness-based enhancements of introspective accuracy are real,” participants may then be self-reporting from a significantly more honest perspective. Gaining insight may make one honestly worse. The data are skewed. Second, the adverse effects are intriguing from the perspective of a “healing crisis” that can happen in whole person care. Peel back a layer and who knows what might emerge. Anxiety may be a good thing. Optimally those offering mindfulness services will have the skills to manage what they awaken. Finally, erring on the side of “hype” will likely be a good thing while this new research agenda is carried out. In our culture, mindfulness may be reasonably viewed as generally wanting. Baby starts, booster shots and transformative practices may all be useful. While we await the new clarity and research precision, I will favor over-medicating with mindfulness and meditation practices, and risking the adverse effects. And I’ll hold to the proposition from the Benson-Henry group that our population health will flourish if everyone, early in life – or later - had a chance to immerse themselves in a multi-week, mindfulness training program. Editor’s note: This analysis article is not edited and the authors are solely responsible for the content. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Integrative Practitioner.

SHARE