Disruptive functional medicine innovation drives value-based future at Cleveland Clinic

By Integrative Practitioner Staff

By Taylor Walsh and Glenn Sabin

By Taylor Walsh and Glenn Sabin

Christensen, one of the nation’s leading authorities on disruptive innovation in business, wrote those words at a time after the early forces of healthcare disruption had started coalescing, around 2000.

He would not have recognized them at that time because they were not dependent upon the technological advances he often cites as the basis for successful disruption. Rather they were, and remain, disruptive in how patients can be most beneficially treated. This evolution has often been painful, and it may yet produce profit, if, as we will see, that disruption establishes value based on quality outcomes, reduced costs and patient satisfaction. The Triple Aim by any name.

Those early disruptive forces in care first stirred in the U.S. in the 1980’s, initially in the form of formal recognition of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities by the U.S. healthcare system. The subsequent growth of clinical businesses and their patient populations (to shocking levels by 1991²) was completely driven by patient preferences and out-of-pocket spending that was not reimbursable.

Today, we know the care that has emerged during this evolution and its embrace by western medicine—integrating once unfamiliar modalities and views of health with medicine’s response to the preponderance of chronic illness and disease—as the proving grounds for integrative medicine (see the following notable examples).

Since 2000, early variations of Christensen’s “focused-hospitals” arose within many traditional healthcare institutions and systems:

- In the establishment of many Centers of Integrative Medicine at U.S. medical schools, growing from eight at its 1999 inception to more than 70 today, and leading to the formation of The Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine & Health, ACIMH.

- The growth of integrative health and medicine in the U.S. Military Health System and especially the VA that began in the wake of the wars in the Middle East, that now influences the approaches to care and healing in these and other major institutions.

- The investment in integrative medicine and health units at academic and non-academic regional and national hospital systems such as Mayo, Allina, Medstar, Sutter Health, Meridian Health and Beaumont Health (many, including the VA, are now members of ACIMH).

If there is a model of disruptive innovation in healthcare that Christensen might recognize today it is probably located at the Cleveland Clinic, where its Center for Functional Medicine (CC-CFM) is as close to a ‘focused-hospital’ bent on deliberate self-disruption as we are likely to find.

Established in 2014 after CEO Delos (Toby) Cosgrove, MD and Mark Hyman, MD, current chairman of the Institute for Functional Medicine, agreed to bring to the Cleveland Clinic functional approaches to identifying root causes of illness and to treating conditions in collaborative fashion.

Behind this decision was the intention to create a sustainable business model based on value that would scale in such a way as to establish new relationships with insurers and make the functional approach a norm in healthcare.

In presentations at the Personalized Lifestyle Medicine Institute (PLMI) conference “Harnessing the Genomic Revolution: Breakthroughs in Personalized Precision Health Care” in October of 2016, Dr. Hyman, now Director of CC-CFM, and Patrick Hanaway, MD, its Medical Director, described the careful, intentional efforts being made to establish this business model grounded in the precepts of the Triple Aim: reduced costs, better outcomes and greater patient satisfaction.

Hanaway described these efforts as, “demonstrating value as we move into an era of accountable care, where our reimbursement in the future will be based on outcome. We can show our outcomes are better, for fewer dollars.”

Ready, Set…Expand Again

Since opening in the fall of 2014, the CC-CFM has grown significantly: expanding its clinical space twice (to 18,000 sq. ft.); enlarging its practitioner staff; and establishing its initial research and data analysis operation. All of which has taken place while serving some 4,200 patients from 38 states and 12 countries, and building a word-of-mouth waiting list that stood at 3,000 in early 2017.

Hyman noted that the clinic was designed to facilitate healthcare transformation not only through how care is provided, but how the transformation presents itself. This includes specially designed clinical space that attained a WELL Building certification, how the provider teams are organized around each patient, and functioning within the Cleveland Clinic as “a virus” by becoming part of its continuum of care across the institution.

The challenge, as it remains for all hospitals, health systems, and academic centers offering mixed conventional and integrative services, is getting paid. Both Hanaway and Hyman had examples of the mismatch between the healing value of their work and the business value that remains to be established.

For instance: Hyman described a 40-year old woman suffering arthritis, reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, depression, and pre-diabetes. Her multiple prescriptions included a drug costing $50,000/year, which she would likely depend on for many years in order to manage her condition.

Hyman said his functional workup identified inflammation and conditions in the gut that he treated. After two months the patient’s symptoms were gone, she was off the meds, and she’d lost 20 pounds. By any measure a great outcome and real value to the patient and to the care system. But not to Cleveland Clinic because the downstream value of the treatment went unreimbursed; in other words, the savings to the system were not recognized.

“We are not reimbursed for the value we’re providing,” he said.

It is an achingly familiar refrain that can be heard across the now rapidly expanding integrative healthcare landscape. (And dealing with this reality is the subject of our preceding article, Institution-based Integrative Medicine: Current Economic Challenges and Opportunities.)

Hyman calls this status, “Reimbursement No Man’s Land,” where volume still takes precedence over value. “We don’t have evidence-based healthcare,” he notes. “We have reimbursement-based healthcare.” In cases like the one Hyman described above, the Cleveland Clinic is filling the payment gap.

The Method

Dr. Hanaway’s presentation described the programs and clinical systems, analytical tools, team-building and research programs being put in place to create this paradigm of value. These include:

- Conducting a select group of small RCTs.

- Working with the Institute for Functional Medicine to standardize clinical protocols.

- Collecting and integrating quality, outcome and cost data (often for the first time ever).

- Collecting patient case studies that illustrate the patient experience.

[Note: Dr. Hanaway’s full presentation (40 min.) is available here on the PLMI web site (requires free registration). Click on the “Day 2” tab.]

In reviewing these efforts in some detail, Hanaway noted, “We’re in a learning process of ‘How do we put these tools together?’ We look at quality, we look at cost, and work toward value.”

A “Total Cost of Care” Trial

Even for this highly touted and innovative unit of the Cleveland Clinic, getting access to claims data was not straightforward. Hanaway reported that CC-CFM had to demonstrate the efficacy of its work and obtain IRB approval for the cost of care trial. Once established, this comparison looked at the number of specialty visits made within a year after an initial clinical encounter made by CC-CFM patients vs. the Clinic’s own standard-of-care patients. CC-CFM patients made two; propensity-matched control patients in the routine care cohort made five.

RCTs are also being conducted in Type II Diabetes, and Asthma.

Outcomes: Function and Cost

In assessing improved function and reduced symptoms, Hanaway noted the challenge this can present for measuring the progress made by patients who are treated for co-morbidities with whole-person approaches that characterize functional medicine. But by using the CG-CAPS patient satisfaction evaluation, he said, the CC-CFM “ranks in the 90th percentile in physician interaction and quality.”

Another measure, using the NIH’s PROMIS-10 tool to compare the results of “clinically significant improvement” from CC-CFM treatments to those of the Clinic’s family medicine unit (CC-FM) (already among the nation’s best for patient clinical improvement), demonstrates the following improvement scores:

- CC-CFM: + 38.7 percent

- CC-FM: + 27.4 percent

In part this nearly 40 percent difference reflects what Hanaway reports as the CC-CFM’s success in encouraging patients to actively embrace activities that support their health (through ‘patient activation measures’). Indicative of this were results from comparisons of patients being treated for fatigue, mood, and autoimmune conditions.

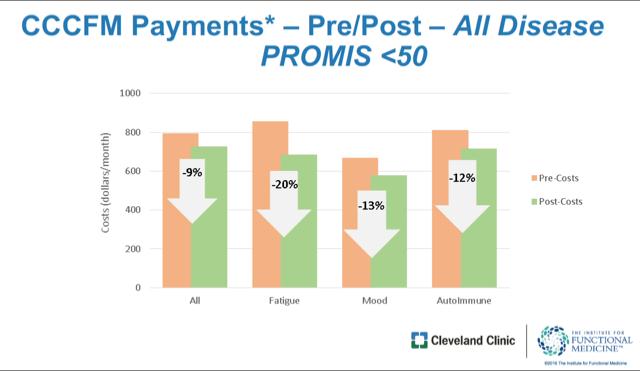

Using the NIH PROMIS scale that measures global function and patient improvement, CC-CFM compared the outcomes for patients first treated for these conditions as standard-of-care Clinic patients over a nine months period, against the costs when treated in the CC-CFM over the next nine-month period. (N.B. Only medical care, labs, and supplements are included in this initial analysis. Total claims data is being sought so that it includes pharmaceutical cost data for pre/post-comparison.)

Hanaway pointed out that it is noteworthy that sicker patients showed greater improvement. For all the conditions, as the chart illustrates, the overall monthly costs were 9% less in the CC-CFM; for fatigue: 20 percent; for mood: 13 percent; for autoimmune: 12 percent.

This illustrates fewer specialty visits needed and less costs for functional treatments compared to the usual standard of care. These data, Hanaway said, “will begin to change the conversation about value…People responsible for revenue (at Cleveland Clinic) will say, ‘We think the first place where we can take risk with the insurance companies is in functional medicine.’ “ He later reinforced this view in an email exchange:

“The demonstration of value is essential. This will allow for shared risk in the future, long before there are rate changes for payment through CMS/HCFA (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services/Health Care Financing Administration).”

“We are in dialogue to gather data and work with Blue Cross/Blue Shield Anthem and will be approaching others after we demonstrate value in those retrospective reviews of cost and outcome.” (CC-CFM is also working with Medical Mutual of Ohio and United Healthcare, among other payers.)

New Partnerships Needed to Achieve Innovative Healthcare Disruption

CC-CFM’s initial results are indeed impressive, and will start, potentially, to move the true value attained in functional medicine into a financial framework that may persuade payers to write coverage plans reflecting that value which is beginning to be shown.

Strengthening this case are examples of related efforts at centers such as the Allina Health system in Minnesota and western Wisconsin that has been tracking data and costs on integrative care for a decade³. Other academic centers of integrative medicine (some members of ACIMH for instance) that also offer clinical services with research components may, likewise, contribute to an expansive measure of Triple Aim-centered value necessary to make that case.

These centers and the CC-CFM quite naturally prefer to develop and prove the value proposition of functional and integrative medicine within their own service areas and markets, working with commercial insurance partners rather than waiting on CMS to change the reimbursement paradigm.

But the role that CMS is now playing is intriguing and needs to be more fully appreciated. CMS has committed to and is investing in Triple Aim-based care through its Alternative Payment Models program ($10 billion since its creation by the ACA). This puts CMS in sync with the commitments to value and to lifestyle-based medicine that the CC-CFM and others have made. This is particularly true when considering the care needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries whose treatments by functional medicine approaches have repeatedly demonstrated clinical and cost effectiveness and patient satisfaction.

The deliberately disruptive model that the Cleveland Clinic and its Center for Functional Medicine have put in place to demonstrate a scalable value for these efforts will be well worth watching, in particular as insurers respond to the results that Drs. Hyman and Hanaway are reporting.

Will they establish best practices in clinical delivery that lead to securing reimbursements commensurate with value, and will that payment model then be exported to related providers? To mid-sized provider organizations? To private practitioner groups and independent practitioners? Will these all have to be physician-led and directed enterprises?

Can the CC-CFM model truly influence the payers and regulators in the states and at long last get out of what Mark Hyman called “Reimbursement No-Man’s Land?” And so close the reimbursement gap? Well worth watching indeed.

References

[ 1 ] – “The Innovator’s Prescription,” McGraw-Hill, 2009; p 105. Christensen is a leading authority on disruptive innovative, the author of “The Innovator’s Dilemma” 1997, and a faculty member at the Harvard Business School.

[ 2 ] – “Unconventional Medicine in the United States—Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use,” David Eisenberg, et al. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:246-252:

[ 3 ] – Allina is one the very few healthcare providing institutions that include integrative medicine services to participate in the CMS Alternative Payment Model program. This important program rewards providing entities whose approaches meet the goals of the Triple Aim, particularly in cost savings. https://qpp.cms.gov