How the National Cancer Plan Fails to Address the Role of Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches

As part of his Cancer Moonshot, President Biden's 25-page National Cancer Plan,1 a “brochure” published in early April 2023, is a typical government groupthink “business as usual” proposal that aims to “end cancer as we know it today” and “revolutionize cancer treatment and research” in the United States. The plan establishes goals, lays out a set of strategies, and has a call to action that covers a wide range of topics, including cancer prevention, early detection, access to care for all Americans, and a brief nod to diet and lifestyle. However, it fails to address the role of complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches in cancer treatment, specifically reducing the side effect profiles of chemotherapy, radiation, and hormonal therapies and improving the quality of life of cancer survivors. Is the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and National Institute of Health (NIH) trapped in a 20th-century medical paradigm, or just completely tone-deaf to state-of-the-art cancer treatment?

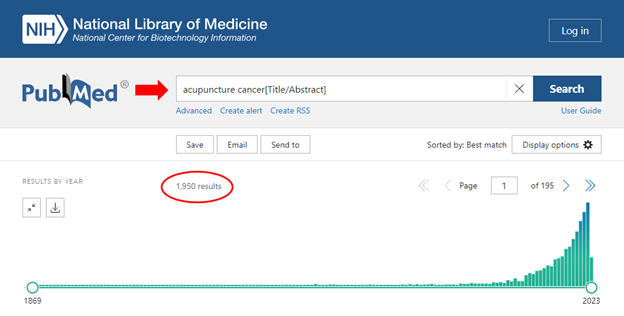

Complementary and integrative health approaches, such as acupuncture, massage/craniosacral therapy, chiropractic, and homeopathy, have been shown to be safe and effective in improving cancer patients' quality of life and reducing the side effects of conventional cancer treatments and are the subject of pragmatic studies at NCI. For example, acupuncture has been found to alleviate chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting,2 neuropathy,3 joint pain,4 and fatigue,5 while massage has been shown to reduce cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients.6 Cancer survivors also greatly benefit from integrative care where the primary focus is on health promotion and disease prevention. Acupuncture, for example, has more than 1,900 studies related to cancer in the NIH PubMed database (Fig 1), and to overlook it in the plan is bordering on criminal.

Figure 1: Number of hits on the NIH PubMed database regarding acupuncture and cancer

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting the use of multidisciplinary approaches in cancer care, the National Cancer Plan makes no mention of these modalities. This omission is concerning since the leading U.S. cancer centers, such as MD Anderson, offer integrative health services that include exercise programs, nutrition counseling, acupuncture, massage, tai chi, qigong, yoga, meditation, and music and art therapy.7 Physicians often recommend complementary health approaches, with 53.1 percent of office-based U.S. physicians recommending at least one to their patients in the past 12 months.8

Patients’ quality of life can be significantly reduced due to the side effects of cancer treatments. They report using complementary treatment strategies for headaches and migraine, dizziness and tinnitus, gastrointestinal disorders, as well as stress-related and mental problems like depression and anxiety.9 In children, complementary and integrative health practices are used to support symptom alleviation of oncological diseases.10 In the United Kingdom and Switzerland, National Health Services cancer centers11 have established treatment concepts combining complementary and integrative health procedures with conventional in-patient and out-patient care.

Complementary and integrative health strategies are used for preventive and therapeutic purposes, addressing a wide range of physical and mental symptoms associated with cancer treatment in all age groups, from infants to older adults. These modalities provide additional safe and effective treatment options for patients undergoing cancer treatment. From a provider and insurer standpoint, supporting the use of complementary and integrative therapies not only improves patient health but also reduces costs.12 One possible explanation for this blatant oversight is the historical divide between conventional medicine and integrative health approaches in health policy and research. Another explanation is that the team chosen to write the plan failed to include a single CIH practitioner or MD or PhD with even a rudimentary understanding of integrative health concepts.

For decades, conventional medicine has been the dominant paradigm in cancer treatment, with little attention paid to alternative therapies. The Department of Veterans Affairs, however, oversees the largest healthcare system in the U.S., where more than 90 percent of its 1,200 facilities offer some form of integrative care in their conscious effort to shift to a Whole Health paradigm. HHS may learn a few things from the VA.

The National Cancer Plan missed an opportunity to acknowledge this shift in the healthcare landscape and embrace the potential benefits of complementary and integrative health practices in cancer care. By ignoring these modalities, the plan risks perpetuating the outdated paradigm of conventional medicine and misses out on the opportunity to provide more holistic and patient-centered care. The Society of Integrative Oncology exists for a reason and has developed a number of practice guidelines for oncologists.13

Furthermore, the exclusion of complementary and integrative health approaches from the National Cancer Plan could have a significant impact on health equity. Studies have shown that access to complementary and integrative health providers is often limited for underserved and marginalized communities, who may not have the financial resources to pay for these services or may not have access to providers who offer them.14 By failing to address this issue in the cancer plan, the DHHS could be perpetuating health disparities that disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

The plan states under "Deliver Optimal Care" that “The health care system delivers evidence-based, patient-centered care to all people that prioritize prevention, reduces cancer morbidity and mortality, and improves the lives of cancer survivors, including people living with cancer.” The words are there, but the intent is not. If HHS intends to put that statement into practice, then one of the strategies would be to "increase communication and collaboration between NCI and other government entities such as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, to capitalize on the data, expertise, resources, and relationships that inform and facilitate cancer research.”

The section goes on to mention cross-agency collaboration and public-private partnerships to improve survivor well-being. Integrative health practitioners focus on health promotion and improvement in well-being and quality of life and are a valuable addition to an oncology center. Furthermore, another strategy listed is to "identify and institute best practices…" while completely ignoring their own doctrine of the HHS Pain Management Best Practices report, where nonpharmacologic approaches like acupuncture, massage, yoga, and chiropractic care are recommended.15 They are, however, pushing for “new vaccines to prevent cancers.”

While the National Cancer Plan is an important and laudable effort to improve cancer care in the US, it falls short by failing to acknowledge the benefits of complementary and integrative health approaches in cancer treatment. The exclusion of these modalities from the plan is concerning, as it perpetuates an outdated paradigm of cancer treatment and misses an opportunity to provide more holistic and patient-centered care, which is the standard at leading U.S. oncology centers. Moreover, the exclusion of safe and cost-effective complementary and integrative health strategies from the plan could have a significant impact on health equity, perpetuating disparities that disproportionately affect marginalized communities. It is essential that the Biden administration reconsiders the role of complementary and integrative health approaches in cancer care and takes steps to ensure that all Americans have access to these modalities.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding statement: The author of this commentary did not receive any grants or financial support from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References:

- The National Cancer Plan, https://nationalcancerplan.cancer.gov/national-cancer-plan.pdf, [Last accessed: 4/17/23].

- Konno, Rie. Cochrane Review Summary for Cancer Nursing: Acupuncture-Point Stimulation for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea or Vomiting. Cancer nursing. 2010;33.6: 479–480.

- Baviera AF, Olson K, Paula JM, Toneti BF, Sawada NO. Acupuncture in adults with Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: a systematic review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2019 Mar 10;27:e3126. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2959.3126. PMID: 30916227; PMCID: PMC6432990.

- Bao T, Li SQ, Dearing JL, et al. Acupuncture versus medication for pain management: a cross-sectional study of breast cancer survivors. Acupunct Med. 2018;36 (2): 80-87.

- Jang A, Brown C, Lamoury G, Morgia M, et al. The Effects of Acupuncture on Cancer-Related Fatigue: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420949679. doi: 10.1177/1534735420949679. PMID: 32996339; PMCID: PMC7533944.

- Kinkead B, Schettler PJ, Larson ER, et al. Massage therapy decreases cancer-related fatigue: Results from a randomized early phase trial. Cancer. 2018;124(3):546-554. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31064. Epub 2017 Oct 17. PMID: 29044466; PMCID: PMC5780237.

- MD Anderson Integrative Medicine Center Clinical Services, https://www.mdanderson.org/patients-family/diagnosis-treatment/care-centers-clinics/integrative-medicine-center/clinical-services.html [Last accessed: 4/17/23].

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RR, Barnes PM, et al. US Physician Recommendations to Their Patients About the Use of Complementary Health Approaches. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(1):25-33. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0303. Epub 2019 Dec 2. PMID: 31763927; PMCID: PMC6998052.

- von Peter S, Ting W, Scrivani S, et al. Survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with headache syndromes. Cephalalgia 2002;22(5):395-400.

- Psihogios A, Ennis JK, Seely D. Naturopathic Oncology Care for Pediatric Cancers: A Practice Survey. Integr Cancer Ther 2019, 18:1534735419878504. 10.1177/1534735419878504.

- Gage H, Storey L, McDowell C, et al. Integrated care: utilisation of complementary and alternative medicine within a conventional cancer treatment centre. Complement Ther Med 2009;17(2):84-91. 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.09.001.

- Martin BI, Gerkovich MM, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Lind BK, Goertz CM, Lafferty WE. The association of complementary and alternative medicine use and health care expenditures for back and neck problems. Med Care 2012;50(12):1029-1036. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318269e0b2

- Society of Integrative Oncology Practice Guidelines, https://integrativeonc.org/practice-guidelines/guidelines [Last accessed: 4/17/23].

- Adkinson, SM, Brandow, A, Clauw, D, et al. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf [Last accessed: 4/17/23].

- Ibid, 41-44

SHARE