Timing is everything part 1: The complexity and clinical consequences of circadian dyssynchrony

January 4, 2017

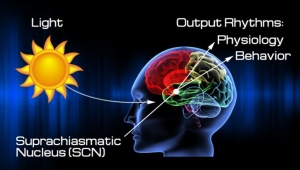

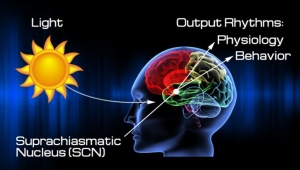

by Lena D. Edwards, MD, ABOIM, ABAARM, FAARM, FICT The daily rotational cycles of the earth result in 24-hour cycles of alternating light and darkness. This rhythm affects the sustainability of life on this planet because it dictates global food availability, temperature, and light intensity. Human beings have evolutionarily adapted to this predictable cycle by creating internal clock systems, which synchronize all metabolic, cellular, and behavioral processes. Extensive research has shown that the functional integrity of the human circadian clock system is a critical determinant of health, behavior, and disease development. In fact, even when other confounding comorbid factors are absent, circadian dyssynchrony can increase an individual’s risk of developing a number of diseases including diabetes, hypertension, a variety of malignancies, and cardiovascular disease, to name a few. Healthcare providers can better counsel and treat their patients when they understand the pathophysiological mechanisms by which ‘being out of rhythm’ can cause widespread physiologic disarray. The central mediator of the circadian hierarchical clock system is the ‘master clock’ located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the ventral hypothalamus. Remarkably, the 20,000 neurons located here are cell autonomous, individually capable of generating their own rhythmic oscillations. However, for optimal central clock function to occur, the SCN relies on a collaborative network comprised of a community of all individual, cell autonomous neurons. The innate function of the human circadian clock system is a genetically influenced; however its functional integrity is mediated by an intricate interplay of exogenous cues, endogenous hormonal mediators, and numerous molecular factors. Many types of exogenous cues, including light exposure (most “potent”), feeding times, physical activity, and sleep habits, can regulate SCN control of circadian rhythm.  There are three essential components of the human circadian clock system.

There are three essential components of the human circadian clock system.  Unlike the cell autonomous networks of the central clock, the cellular networks of peripheral clocks are not autonomous, and thus rely on consistent communication with the central clock to synchronize with each other, and with the SCN. Since the discovery a little over a decade ago, ongoing studies of peripheral clocks have shown that they are extremely influential in coordinating numerous aspects of organ function. In fact, peripheral clocks regulate such a wide range of metabolic processes— including lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and detoxification pathways—that any dyssynchrony with each other, or with the central clock, can directly impact an individual’s thoughts and behaviors, as well as their overall health and predilection for disease development. The ultimate downstream hormonal mediator of the SCN induced circadian rhythm is cortisol. Due to its global physiologic authority over all bodily functions, cortisol serves as the key time-keeping chemical messenger. Regulation of cortisol secretion mandates global physiological and cellular function, and also affects the ongoing functional integrity of the circadian rhythm itself. There are three main pathways through which SCN stimulation induces cortisol release and regulation:

Unlike the cell autonomous networks of the central clock, the cellular networks of peripheral clocks are not autonomous, and thus rely on consistent communication with the central clock to synchronize with each other, and with the SCN. Since the discovery a little over a decade ago, ongoing studies of peripheral clocks have shown that they are extremely influential in coordinating numerous aspects of organ function. In fact, peripheral clocks regulate such a wide range of metabolic processes— including lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and detoxification pathways—that any dyssynchrony with each other, or with the central clock, can directly impact an individual’s thoughts and behaviors, as well as their overall health and predilection for disease development. The ultimate downstream hormonal mediator of the SCN induced circadian rhythm is cortisol. Due to its global physiologic authority over all bodily functions, cortisol serves as the key time-keeping chemical messenger. Regulation of cortisol secretion mandates global physiological and cellular function, and also affects the ongoing functional integrity of the circadian rhythm itself. There are three main pathways through which SCN stimulation induces cortisol release and regulation:

There are three essential components of the human circadian clock system.

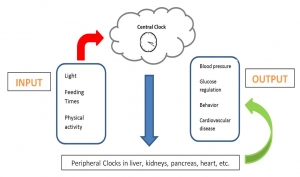

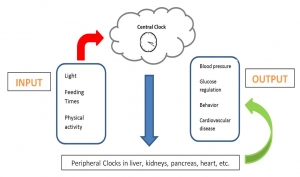

There are three essential components of the human circadian clock system. - The input pathways, which receive and relay exogenous cues to the brain

- A central circadian clock in the SCN, which maintains the circadian rhythm (“master clock”)

- Peripheral clocks within individual organs, which control the physiologic, behavioral, and metabolic end responses

Unlike the cell autonomous networks of the central clock, the cellular networks of peripheral clocks are not autonomous, and thus rely on consistent communication with the central clock to synchronize with each other, and with the SCN. Since the discovery a little over a decade ago, ongoing studies of peripheral clocks have shown that they are extremely influential in coordinating numerous aspects of organ function. In fact, peripheral clocks regulate such a wide range of metabolic processes— including lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and detoxification pathways—that any dyssynchrony with each other, or with the central clock, can directly impact an individual’s thoughts and behaviors, as well as their overall health and predilection for disease development. The ultimate downstream hormonal mediator of the SCN induced circadian rhythm is cortisol. Due to its global physiologic authority over all bodily functions, cortisol serves as the key time-keeping chemical messenger. Regulation of cortisol secretion mandates global physiological and cellular function, and also affects the ongoing functional integrity of the circadian rhythm itself. There are three main pathways through which SCN stimulation induces cortisol release and regulation:

Unlike the cell autonomous networks of the central clock, the cellular networks of peripheral clocks are not autonomous, and thus rely on consistent communication with the central clock to synchronize with each other, and with the SCN. Since the discovery a little over a decade ago, ongoing studies of peripheral clocks have shown that they are extremely influential in coordinating numerous aspects of organ function. In fact, peripheral clocks regulate such a wide range of metabolic processes— including lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and detoxification pathways—that any dyssynchrony with each other, or with the central clock, can directly impact an individual’s thoughts and behaviors, as well as their overall health and predilection for disease development. The ultimate downstream hormonal mediator of the SCN induced circadian rhythm is cortisol. Due to its global physiologic authority over all bodily functions, cortisol serves as the key time-keeping chemical messenger. Regulation of cortisol secretion mandates global physiological and cellular function, and also affects the ongoing functional integrity of the circadian rhythm itself. There are three main pathways through which SCN stimulation induces cortisol release and regulation: - Activation of the HPA axis with subsequent ACTH dependent cortisol release

- Direct neural connection between the SCN and the adrenal gland via the autonomic nervous system (ANS)

- Direct photic stimulation of the adrenal glands via SCN-ANS pathway, through catecholamine induced splanchnic nerve stimulation

SHARE